01 Apr The Value of the Beef Carcass in Modern Japanese Cuisine

Japan Trip Report by Kristy Walters

The value of beef in modern Japanese cuisine has an interesting story.

With historical records dating the introduction of the domestic cow into Japan between 500BC and 300AD (Minezawa, 2003), cattle were originally used as ploughing power in the mining, forestry and agricultural trades. It is assumed that cattle were consumed as a source of protein to some extent, however introduction of Buddhism, and the religious teaching of reincarnation, led to the social taboo against the consumption of beef by 550AD. In 675AD, this made law by Emperor Tenmu with a prohibition against the slaughter and consumption of cattle extending from the period of April to September, which was gradually extended to year-round and enforced by succeeding emperors up until the 10th century (Watanabe, 2004). Punishments for breaking this law were up to 100 days fasting for one who was caught consuming beef.

As Christianity spread across the globe in the 14th century, the Japanese became intrigued by the health benefits and exotic beef dishes that accompanied the arrival of the patron saint Francis Xavier to the country in 1549. After a brief stint of adoption of Christianity and the return of meat-eating in the diet, both were banned in 1620 as threats to national unity and traditional Japanese values (Jansen, 2000). The saga was eventually broken by the Emperor Meiji in 1872, whose public consumption of beef ended what was generally regarded as a 1 200-year ban and encouraged all social classes to once again adopt the protein source into their diet.

The average Japanese person now consumes 5.9kg of beef a year (e-Stat. 2014).

This report does not aim to re-write the history of Japanese beef production in detail. I do feel however that the above is important for appreciation of the varied role that beef has played over time in the lives and diet of the Japanese from beast of burden to religious sacrality to absolute protein source.

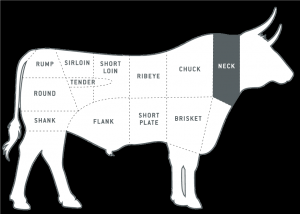

Having little to no experience with Japanese cuisine prior to this tour, a topic that was extremely interesting and one that I believe has value in being shared is the breakdown of the beef carcass into modern Japanese dishes. Therefore, the aim of this report is to analyse the carcass featured below (Image 1) and detail the use and preparation of each cut working from anterior to posterior.

An important point to note is that beef consumption in Japan has a strong emphasis on quality over quantity. With Wagyu beef grading up to a Beef Marbling Standard (BMS) of 12, or 56.3% fat, beef dishes are commonly made up of thinly sliced pieces of beef that are cooked quickly over high heat in the form of flame or boiling water. The resulting product is a small piece of beef that is hot, full of flavour and instantly melts in the mouth upon consumption.

Figure 1 The Wagyu Carcass (Photo credit: First Light Meat Club)

Figure 1 The Wagyu Carcass (Photo credit: First Light Meat Club)

Tongue (Gyutan) – yakiniku

One of the more unusual cuts, the tongue has a distinct, rich flavour that makes it a common ‘starter’ piece in yakiniku with the bold flavour remaining uncontaminated by other cuts. Sliced carpaccio-thin and cooked very quickly over the high heat, the tongue is considered one of the delicacy pieces of the carcass in Japan. (Image 2: Shibuya, Tokyo).

Neck – mince

The neck meat is a combination of lean, fat and connective tissue separated from the chuck by a parallel line right down to the first rib. Grinding this piece into mince is the most common option, as the high levels of fat result in juicy and flavoursome dishes without the need to cook for long periods of time to break down the gelatinous component. (Image 3: Shinjuku, Tokyo).

Chuck (Zabuton) – stewing, sukiyaki, yakiniku

A boneless piece prepared from the removal of the neck meat and cube roll, the chuck is made

up of a variety of muscles, predominately the M. longissimus dorsi. The anterior end joining with

the neck meat remains high in connective tissue and is commonly used in slow-cooking methods

such as sukiyaki. The posterior end joining with the cube roll is of a higher quality, and features

in yakiniku towards the end of the meal as affordable thinly sliced pieces full of flavour and

tenderness.

Brisket –stewing, gyudon

A boneless piece prepared from the removal of the chuck, plate and fore shank and containing the pectoral muscles responsible for supporting the weight of the forequarter. Contains a high level of connective tissue which requires long periods of time in stewing dishes to break down. Increasing in popularity in street food dishes such as beef bowls (gyudon), which are a mixture of pulled brisket and onion with raw egg over a serving of rice.

Cube Roll – shabu shabu, steak

Prepared from the forequarter between the chuck and the striploin, the cube eye (or more commonly referred to as the rib eye in Japan) consists of the M. longissimus dorsi and a few underlying muscles. One of the highest quality cuts from the carcass, the cube roll is renowned for tenderness, fine texture and being full of flavour. It is commonly featured in shabu shabu dishes as very thin slices of highly marbled pieces that require only a few seconds of cooking

before being consumed as rare. (Image 4: Obihiro, Hokkaido).

Oyster Blade (Misuji) – yakiniku, sukiyaki

Removed from the blade in the forequarter, the oyster blade features distinct parallel lines of gristle running through the M. infraspinatus. With a rich, strong flavour, this versatile cut can be found anywhere from half-way through a yakiniku meal to the feature meat within a traditional hot pot in a sukiyaki meal.

Outside Skirt (Harami) – yakiniku

Taken from the plate area of the carcass and forming part of the diaphragm muscle, the outside skirt is a very lean piece that commonly follows the tongue in yakiniku. The leanness, and lack of flavour, of this piece is normally compensated with a miso or soy sauce called tare for dipping the meat into after grilling.

Short Rib Plate (Karubi) – yakiniku, shabu shabu, sukiyaki

Removed from the plate area of the carcass, the muscle is separated from the bone to produce thin pieces of alternating layers of meat and fat. Full of flavour and juice, this piece is very prominent in the yakiniku style of cooking and commonly ordered by tourists and locals alike as thin slices of meat cooked half-way through the meal. Karubi can also be found in shabu shabu or sukiyaki dishes in traditional restaurants through-out Japan. (Image 5: Shibuya, Tokyo).

Striploin – steak, shabu shabu

Prepared from the hindquarter between the cube roll and the rump, the striploin is another of the highest quality cuts to come from the overall carcass. Cooked in a similar fashion to the cube roll, striploin is commonly seen in shabu shabu as thinly sliced, highly marbled pieces that melt in the mouth after only a few seconds of immersion in boiling water. Presented in supermarkets as thin slices 2-3mm in width and individually wrapped in packaging, the consumer will pay up to ¥10 800, or the equivalent of AUD$132, for only 100g of this cut. (Image 6: Sapporo, Hokkaido).

Tenderloin – tataki, shabu shabu

Lying ventrally adjacent to the striploin on the underside of the vertebrae in the hindquarter, the tenderloin is renowned in Japanese culture for its tenderness. It is the most common cut used in tataki, a similar style to sashimi where thin, carpaccio-style fillet pieces are lightly seared to rare and consumed with a citrus-soy dipping sauce termed ponzu. Made up of below average fat both subcutaneously and intramuscularly, the tenderloin is also commonly marketed for shabu shabu dishes as the ‘healthier’ option in comparison to a fattier piece such as cube roll.

Rump – roasting, stir frys,

Located in the hindquarters and comprising the three gluteal muscles within a network of defined

connective tissue, the rump is commonly used as a roasting piece for a family meal. With moderate marbling yet carrying a strong flavour, the rump can also be used as a more affordable cut for the everyday family in dishes as beef strips in stir frys along with udon or soba noodles. Round – roasting, yakiniku, stewing After the removal of the rump, the round is a large primal containing the outside round, (outside flat and eye round), inside round (topside) and sirloin tip (knuckle). Extending further down the hind limb with greater movement, the levels of connective tissue begin to increase in this cut which reflects the varying cooking styles. The topside can be found in a combination of meals from grilling whole over the yakiniku flame before finishing off as sliced pieces (Image 7; Image 8: Shibuya, Tokyo), or in slow-cooked hot pots in a combination of traditional sukiyaki and Westernized diced beef curry dishes (Image 9: Sapporo, Hokkaido). The outside and knuckle are also versatile and used in a family roast or slow-cooked as strips to break down high levels of

gelatinous material.

Shank (Makura) – stewing, sukiyaki, mince

Prepared as a boneless cut consisting of the A-F muscles surrounding the fore and hind shin, the shank contains an extremely high level of connective tissue and requires a long cooking time to break down the gelatinous component. The shank is either ground into lean mince beef, containing minimal fat in its natural state, or trimmed into strips and used in the hot pots of sukiyaki both in the home and at restaurants.

In summary, each part of the beef carcass plays an integral role within Japanese modern culture and the preparation of both traditional and Western dishes. With greater utilisation and cooking methods specific for the physical characteristics of each cut, the breakdown of the carcass is an extremely interesting exercise in understanding and appreciating the value of the beef carcass in modern Japanese cuisine.

- Figure 2 Tongue (Gyutan) prepared for yakiniku

- Figure 3 Neck mince available in a supermarket

- Figure 4 Cube Roll prepared for shabu shabu

- Figure 5 Short Rib Plate (Karubi) grilling over a yakiniku flame

- Figure 6 Striploin individually sliced and wrapped in supermarket

- Figure 7 Topside roasting as a primal over the yakiniku flame.

- Figure 8 Topside slices for finishing over the naked flame.

- Figure 9 Diced Topside after slow-cooking in a hot pot.

References:

• e-Stat (2014). Beef consumption by year in Japan. Hatena Blog. Online at: http://nbakki.hatenablog.com/entry/2014/05/05/233021

• Jansen, Marius (2000). The Making of Modern Japan. Harvard University Press.

• M, Minezawa (2003). Cattle genetic resources in Japan: One successful cross-breeding story and

genetic diversity erosions. Cattle Genetic Resources in Japan. Online of:

http://australianwagyuforum.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/JPbookChapter2Cattle_4.pdf

• Meat and Livestock Australia (2016). Market Snapshot – Beef. MLA. Online at:

• https://www.mla.com.au/globalassets/mla-corporate/prices–markets/documents/os-markets/redmeat-

market-snapshots/mla-japan-beef-snapshot-2017.pdf

• Z, Watanabe (2004). The meat-eating culture of Japan at the beginning of Westernization.

Kikkoman. Online at: https://www.kikkoman.co.jp/kiifc/foodculture/pdf_09/e_002_008.pdf